Sunday 3 May 2020

Lives versus livelihoods

Saturday 2 May 2020

How inductive reasoning failed me with coronavirus

In February, I began writing a blog post saying that coronavirus would turn out to be a storm in a teacup, and although a few people would die - I estimated no more than 10,000* worldwide - it would really be nothing to write home about. I was going to wait until the virus had blown over, then write a critical piece about moral panics and how the media should stop striking fear into our hearts unnecessarily.

* 10,000 really isn't that many, when you consider that over 55 million people die each year anyway.

|

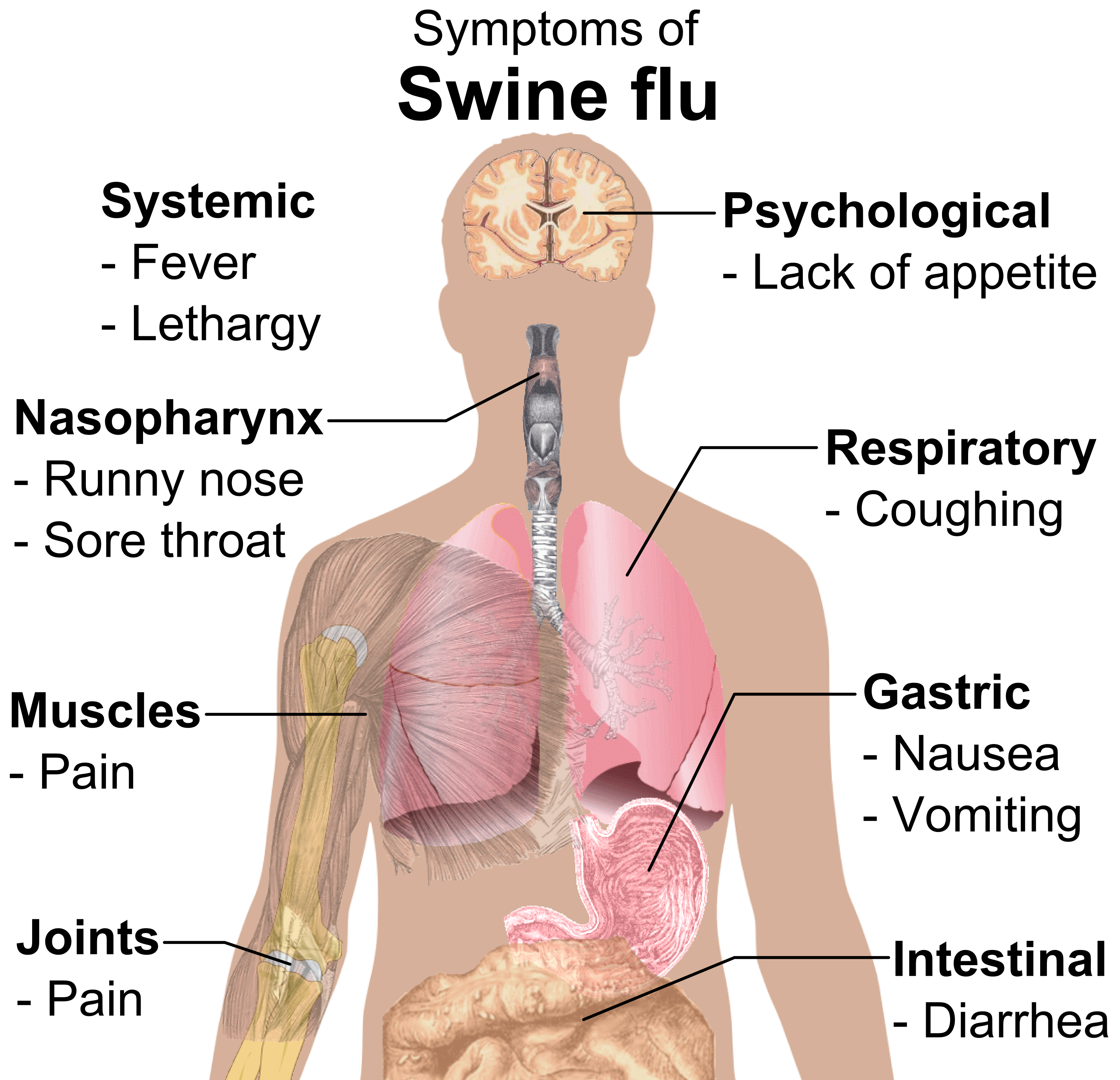

| Swine flu symptoms Source: Wikimedia commons |

Goodness me, I was wrong. I was so, so wrong.

Why was I so wrong?

The problem was that I used inducive reasoning:

A pandemic has never happened in my lifetime, therefore a pandemic won't happen now.

It sounds ridiculous when you say it like that, but that really was my reasoning. There have just been so many times - particularly in the last 20 years or so - that the UK media have spotted a new illness spreading in a faraway country and created a moral panic. They said that a deadly pandemic was on its way, and we should be afraid - very afraid. But then virtually nothing happened to us.

Perhaps when I was a teenager or young adult I was more concerned by these warnings, but as these warnings kept occurring, and with little effect on my life in the leafy suburbs of England, I began to see these pandemic warnings as just more background noise from the media. Bad news is good news in the world of newspapers, and so of course they would leap on any virus and attempt to needlessly whip up the panic among us - it sells papers (or brings in clicks).

Deadly viruses are bad for the communities which suffer them, of course, and I have every sympathy for those who suffer. But so few of them touched the UK in any way that life went on pretty much as normal for us throughout the times of these other viruses, meaning that the UK media were simply scaremongering and sensationalising, as usual.

So by about 2010, any time the media warned about a pandemic, I mentally switched off. They had said that x would cause a pandemic and it didn't; now they were saying that y would cause a pandemic. Based on experience of x being a storm in a teacup, I could be reasonably sure that y wouldn't be a pandemic either.So when a new coronavirus began spreading around Wuhan in January, and the UK papers warned of a worldwide pandemic, I thought it would be yet another pandemic-cum-damp-squib. I was sure it would fizzle out just as the others did, without any change to life in Little England. The media had 'cried wolf' so many times before with other illnesses that I just didn't believe their pandemic warnings any more.

I was wrong not to believe them. This time the 'wolf' was real, and it was about to huff and puff and blow the world down.

Now here we are, with nearly 30,000 deaths in the UK, and over 200,000 dead worldwide, and the virus is showing no signs of abating. Everything in the UK is shut, including schools, offices, shops, leisure centres, and entertainment venues, and we aren't allowed to meet friends or family.

The failure of inductive reasoning

Inductive reasoning led me to believe there wouldn't be a pandemic, and even if there was, it wouldn't hit the UK.

As philosophers, we know that inductive reasoning is weak. All swans are white until you see a black swan. But in life, our experience shapes our way of thinking, and helps us to extrapolate future events based on the past. If Paul has always lied in the past, it'd be silly for me to believe him now. If whenever I lend money to Bryan he doesn't repay me, it would be naive and gullible of me to keep lending him money. So we simply must learn from the past. I think it was George Santayana who said:

Those who cannot learn from the past are doomed to repeat it.

I had learned that when the press warn of a pandemic, it doesn't occur. Now I've learned that sometimes, it does occur.

How bad will covid-19 be?

For the world and the UK, it's going to be horrendous. It already is horrendous, and few if any countries are over the hump yet. On a personal level, I'm just going to keep myself to myself, maintain social distancing, and self-isolate if I have symptoms. I doubt that I'll be in any real danger from the virus if I do catch it. After all...

I've never died before, therefore I won't die now.